One of the most interesting things about the data that we have been collecting – data that many of you have been contributing to by answering our questions each week – is that it allows us to see what is changing for people over time, which people are displaying these changes, and what events prompt changes to occur.

In addition to the question of how well-being is affected by the current situation – the subject of our last blog post – there has been a lot of debate among politicians and in the media about how long people can maintain the levels of social and physical distance that they are being asked to at this extraordinary time. Indeed, the idea that people might find these measures very hard was one factor that influenced other governments (e.g., Prime Minister Boris Johnson in the UK) to delay taking the kind of measures that were very quickly imposed in Denmark.

Human beings are a fundamentally a social species, and there is a lot of evidence that shows how important social contact is for our physical and mental health and wellbeing. With that in mind, not being able to see friends and family, and not being able to interact with them freely and without concern, is something that could eventually become too much for people to bear.

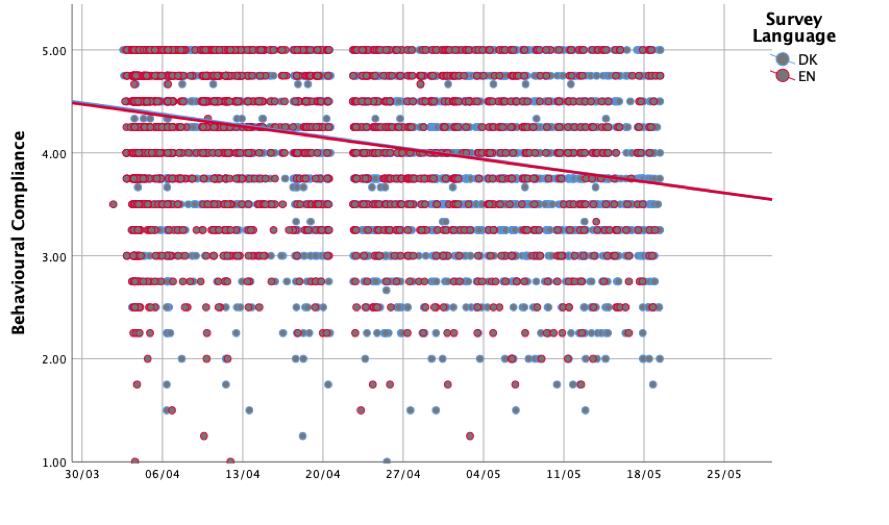

Consistent with that idea, in the data that we have collected so far, we do see a gradual decline over time in people’s self-reported compliance with each of the behavioral recommendations of health authorities: staying home, not attending social gatherings, maintaining distance from others, and washing hands more often than usual. As Figure 1 below shows, this decline is equally present across people who responded to our survey in both Danish and English.

Interestingly, the degree to which people do say that they are complying with these restrictions is associated with their mental and physical health: Higher levels of compliance are associated with worse reported physical and mental health. The relationships between behavioural compliance and reduced well-being also appear to become stronger over time. Patterns like these speak to the accumulating burden of restricted behaviour.

But even if social and physical distancing are burdens, they are also burdens that we are supposed to be enduring for a good cause: this is what we are being asked to do by community leaders (i.e., the Queen, the Prime Minister and the Parliament) to protect the health and well-being of the community as a whole. Along these lines, in our data there is also some evidence that how people feel about the community, and about Parliament, matters for behavioral compliance and for their feelings in the current situation.

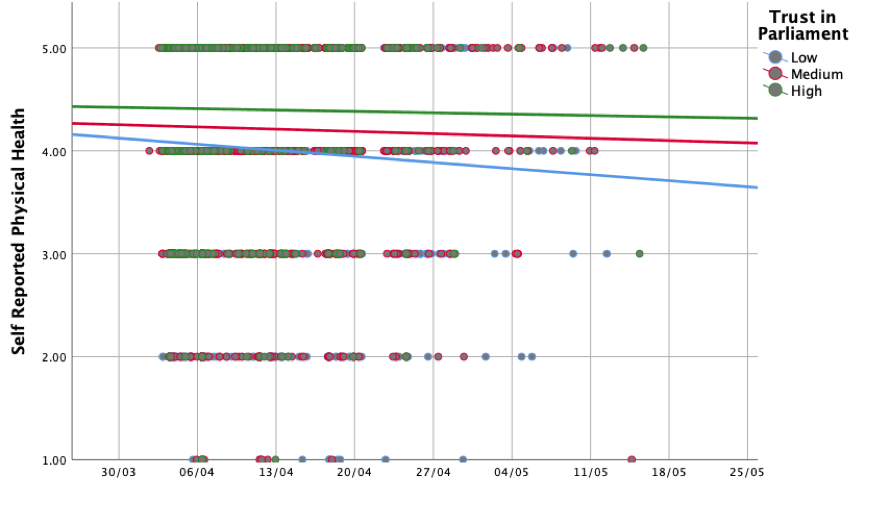

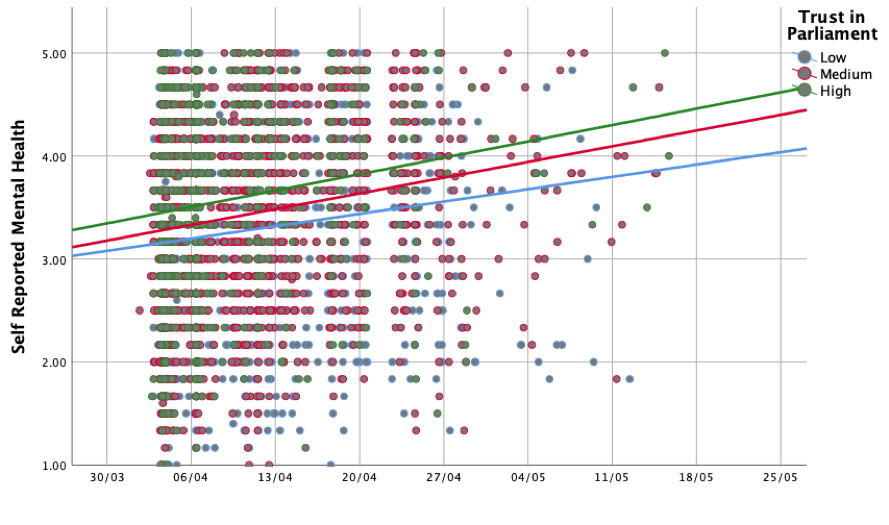

People who report more trust in Parliament are more likely to also say they are complying with recommended behaviour and to be maintaining this behaviour over time. Trust in Parliament is further associated with better maintained physical health over time (Figure 2) and improved mental health over time as well (Figure 3) over time.

So, it seems that trust in society and in political institutions is something that might make it easier for people to cope with the sacrifices they have been making over the lockdown period.

As usual, these are preliminary analyses that have performed on the data and they need to be subjected to more rigorous tests to determine their reliability. But for now, the patterns in the data point to some interesting connections among social trust, behavioural compliance, and individual health and wellbeing.

It will be interesting to see how these connections develop as we enter this new phase in the opening up of Danish society, one in which the official restrictions on behaviour are relaxing to a certain degree and in some areas, but the need for maintained awareness and a degree of caution among the population also remains.

Thanks to the Corona Diary, we will hopefully be able to find out more about these questions. And you can help us by participating:

Link to Danish study: here

Link to English study: here